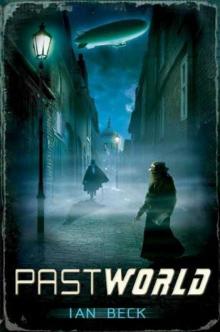

Pastworld Read online

Page 6

That morning, during his first immersion, Caleb’s eyes darted this way and that. He was confused by so many things at once. The haste and hurry, the constant noise from the heavy traffic. The clattering and clopping hooves of the horses, the metal jingle of harness. There were steaming piles of grimly unhygenic manure in the roadways and it seemed there was a constant wash of horse piss in the gutters. Caleb could almost feel the germs rising in the steam, crawling over everything, the twisted writhing colonies of bacteria spilling from cobbles to shoes, from shoes to clothes, from clothes to flesh, and he shuddered.

Caleb watched the overwhelming crowds of poor people as they moved among the smarter Gawkers and residents. He was surprised by their noise and robust roughness, by their numbers, by the variety of their skin colours, and by their bewildering speed of movement and confidence as they dodged around each other on the pavements. With all the shoving and pushing, Pastworld already looked a dangerous place. For some perhaps even a terrifying one. To a skinny seventeen-year-old boy from a dull, wealthy garden city there was an immediate sense of lawlessness and adventure in the air. It seemed to Caleb that almost anything might and could, and perhaps indeed should, happen.

.

Chapter 10

The hansom cab pulled up outside a tall Georgian house in Cloudesley Square, Islington, which was just north of the centre of the old city.

Caleb noticed his father’s anxiety. It became visible just for a moment as they arrived at their lodging house. Another ragged man stepped forward out of the mist and helped the driver down with the steamer trunk. The man then dragged the heavy trunk up the short steps to the front door. After that he stood wringing his hands, waiting to be tipped along with the cab driver. His father looked the beggar up and down, took in his shabby coat, his leaky boots. He gave the beggar a coin; the beggar looked down at the coin and then back at Lucius Brown then, stepping forward close to him, he looked Lucius in the eye.

‘That was a heavy case, very heavy,’ he said quietly, almost mournfully. Then the beggar pocketed the coin, spat on to the ground and, grumbling under his breath, moved off through the mist.

‘Unofficial he was guvn’or, for sure,’ said the cab driver, pocketing his fare and his own generous tip, while doffing his hat. ‘They’re the ones you want to watch out for when you’re out and about in the City,’ and he clicked his horse forward.

‘Unofficial,’ Lucius muttered, and he covered his eyes with his hands and stood silently for a moment as if transfixed to the spot. Caleb noticed that his father’s hand was trembling, like someone suffering from stage fright. After a moment Lucius braced himself, stepped forward and banged on the front door of the house.

‘Mrs Bullock,’ said Lucius, doffing his hat and bowing slightly.

‘Why, yes, indeed, Mr Brown and son, is it not?’ said the pleasant elderly woman in a long brown dress who had opened the door. She stood aside and ushered them into the hallway. Lucius introduced Caleb, who tried an awkward, shallow bow himself, and smiled as best he could.

‘My,’ said Mrs Bullock, ‘what a handsome young man. You’d best watch out for all the young ladies with him, I think, Mr Brown.’

Caleb blushed and looked around at the busy decor of the hallway. The walls were patterned over with dark foliate wallpaper. Pictures in heavy frames hung on gold chains from the picture rail. A white marble bust of Queen Victoria stood on a marbled column beside a fancy hallstand stuffed with umbrellas. There was a smell here too – of lavender overlaid with boiled vegetables.

Mrs Bullock picked up two big cream official envelopes from the post table.

‘These were forwarded here and have been waiting for you,’ she said, ‘and there were two boxes delivered by Carter Patterson. Proper Corporation red wax seal on those envelopes, I noticed. You are clearly important men Mr Brown, Master Brown.’

‘Once upon a time perhaps,’ Lucius replied, tilting his head.

She nodded at them deferentially, while performing a sort of curtsy.

‘It’s not every day that I have an esteemed Buckland Corporation official to stay in my lodging house.’ She turned and flicked her feather duster over the ornaments above the umbrella stand.

‘Thank you for looking after everything so nicely, Mrs Bullock,’ Lucius said. ‘Now if you’ll excuse us, it’s been a tiring journey.’

‘Where are my manners!’ she said. ‘Your rooms are on the first floor at the front, straight up the stairs. I’ve lit a fire for you and there’s plenty of hot water. You won’t be disturbed.’

Lucius clicked the door shut behind him. He leaned against the tapestry draught curtain and closed his eyes. He stayed like that for a moment with the envelopes tight in his hand.

‘What are the letters?’ Caleb asked.

‘They’ll be our invitations, of course,’ Lucius said, going over to warm himself at the coal fire. ‘The big Halloween fancy dress party to be given by Abel Buckland himself, my old boss and the CEO of the Buckland Corporation, which is tomorrow night.’ Lucius proudly displayed the invitations. They had a giant engraved skull and crossbones on one side and the Pastworld logotype on the other. Lucius ran his finger over the engraving. The lines were proud of the surface, raised like a series of bumps.

‘Proper engraving you see,’ Lucius said before he placed them side by side on the overmantel. Then with his back half turned he took out another letter, but this time from his inner pocket. Caleb watched him open it and read it to himself. A curious expression passed across his father’s face in a split second; a pure and sudden wave of anguish. The expression passed quickly, but not quickly enough for Caleb not to notice it. He had caught sight of one word scrawled in big letters across the paper. He could make no sense of it. His father threw the screwed-up letter into the fire, and then he stood, with his head bowed, leaning on the mantel and watched the ball of paper burn through until it was nothing but blackened ash. He picked up a heavy brass poker from the fender and broke the blackened ash down further, thrusting the fragments deep down among the glowing embers of the coal.

‘What was that all about?’ Caleb asked.

‘Oh,’ said Lucius, ‘nothing really – a silly note that was in the pocket of this suit here. You can show some interest then; you do have a tongue when it suits you.’

‘What?’ Caleb protested.

‘We have driven through the streets of this most remarkable city,’ said his father, who seemed suddenly and inexplicably cross. His trembling hand held the heavy brass poker out towards Caleb almost like a weapon. ‘A great technical achievement, one of the great wonders of the modern world and much of it due in no small measure to my efforts, and you have said what exactly? Nothing or next to nothing, no comment at all. I despair of your generation, my boy, sometimes, I really do.’

‘I was looking at everything. You saw me, I was trying my best to take it all in,’ said Caleb, puzzled by the clenched fury of the outburst. It was so unlike his father and to Caleb it seemed that he was lashing out in anger because he was upset. What was his father frightened of? What did the letter mean, that one word? And why burn it like that, as if it was diseased, as if it might attack him? Caleb knew instictively that something was up, something connected with the letter. But he said no more about it.

His father switched attention to the boxes. They contained two Halloween costumes, each specially tailored to their measurements. His father’s was a formal black Victorian suit except it had the bones of a skeleton printed all over the outside front. It was to be worn under a long cape, so that the white of the bones would only show properly when the cape was swirled open or removed. Caleb’s box contained a similar formal suit but without the bones printed on it. Instead, he had been supplied with a skull mask to wear. The crumpled skull grinned back at him, making the box with the neatly folded suit inside look like a miniature coffin.

Caleb was still getting used to the stiff and awkward Victorian clothes they had to wear. He got undressed in his little bedr

oom, which was made to feel smaller by the decoration, more foliate-patterned wallpaper, more pictures in gold frames, watercolours of highland cattle, and views of the Pyramids. He was looking forward to a dreamless night in the old-fashioned brass bedstead.

He had been fidgeting with the clothes all day, fussing with the trousers which were worn high up on the waist, held up by tight elastic braces that pressed down on his shoulders. The hard leather ankle boots had hurt his feet. He hung the jacket on a hanger next to the velvet-collared top coat, and the deep buttoned waistcoat. This white shirt had the devilishly difficult to fix, detachable and very stiff collar, which had left a red itchy weal around Caleb’s throat, and which was held in place, front and back, with solid gold studs.

He brushed his teeth at the sink, dabbing the brush in the round tin of dentifrice, which tasted strongly medicinal. He looked up at himself in the mirror. His hair was flat with pomade, there were red marks on his shoulders where the braces had rubbed; he hardly knew himself.

His father woke him early. ‘Authentic breakfast,’ he said.

The morning papers were laid out in a fan shape on the side table at breakfast. Caleb’s father ignored them as he ate his way through a bowl of porridge. Caleb picked up a London Mercury. There was a dramatic engraving of a sinister-looking man in a cape, a tall hat, and a black face mask. Caleb held out the picture to his father and read aloud the headline caption. ‘“The Fantom is back. New victim found in Shoreditch, with severed limbs and head removed. The head was later recovered from the top of a building scheduled soon for grand public demolition,” it says here.’

His father looked up hurriedly, nervously, and then as if trying to distract Caleb away from the subject. ‘The Fantom,’ he said, ‘will no doubt prove to be an actor like all the others working for the Corporation. It’s all a bit cheap really, isn’t it.’

‘Hanging would be much too good for him,’ Mrs Bullock said as she bustled in and acknowledged the image with a shudder. She laid down two full plates of bacon and eggs. ‘He used to rob banks, they say, as if that wasn’t bad enough, but now it’s much worse. They say he takes out their hearts and the like.’ She shuddered and then offered them a fresh pot of tea and another round of toast.

.

Chapter 11

Later that afternoon Caleb stood in the window of the upper sitting room of the lodging house. His new, crisply tailored suit clung to his thin frame. He looked elegant, like a young man about town, or a ‘swell’, as they were known. He stood as still as one of the Sunderland china figures lined up along the chimney mantel, watching his father fuss with his own clothes in the bathroom behind him.

‘There, I’m ready,’ said Lucius, finally bustling in through the connecting door. ‘Turn round then, Caleb. Let’s have a good look at you.’

Caleb turned from the window and his father gasped. It looked to Caleb as if his father had just seen a real ghost, had a sudden shock of recognition. In his severe black suit and high white collar with his blazing sea-blue eyes clearly lit, Caleb looked suddenly like someone else altogether.

‘Well,’ Caleb said, ‘what’s the matter?’

‘Nothing, my boy, nothing at all,’ said his father. ‘Sorry, but for a moment you reminded me of someone, that’s all.’

There was a loud knock at the front door and in a moment Mrs Bullock called up the stairs.

‘Hansom’s here, Mr Brown.’

‘Thank you,’ Lucius called down. ‘Come on now, Caleb, look lively. At least we shall travel on a steam train, you might enjoy that,’ and he rubbed his hands together as if delighted at the prospect, but Caleb noticed that there was still a look of anxiety and fear behind his father’s eyes.

Outside the local railway station at Highbury Corner Caleb saw close to the day to day realities of a city run on horse power. Cab and dray horses were lined up at the crossing place. Caleb had hardly ever seen a real horse before and now here were dozens of them. They steamed, they stamped, they shook their heads, spraying saliva in sticky gobbets. They pissed and shat where they stood or as they walked. Their lips curled back and showed their big teeth. They weren’t even still while they waited, but jerked forward or scraped their hooves on the cobbles. It felt risky just standing close to them.

They sat in one of the many retro-furbished suburban steam railway trains. It was Caleb’s first such journey. It felt very odd to travel so slowly. The train felt not only noisy, but, he thought, thrillingly aggressive. As the houses slipped by, Caleb breathed in and savoured the trails and ribbons of steam, and the flecks of dark soot smuts which flew in through the half-open window.

His father broke through his thoughts. He had seen a glimpse of the murky river through the steamed-over window. He leaned across and rubbed a clear space free in the glass, and pointed it out. ‘There,’ he said tapping the window. ‘The house we need to get to for the party is somewhere south, and near the river down there.’

While the doors were slammed heavily shut, the train stood like a great creature breathing out chuffs, bursts, and sighs of steam. Caleb turned away reluctantly.

They left the foggy platform and went down some stairs. A slippery, dingily lit, tiled connecting tunnel linked the twenty or so railway platforms below ground. The great steam trains rumbled overhead. An excited Gawker, who was dressed head to foot in black and wearing a long flowing opera cloak, waved a silver dagger above his head. He had a black mask all over his face, and was making his way annoyingly and deliberately against the flow of the other passengers. He looked over at Caleb and pointed his fake dagger as he passed and laughed. He called out, ‘I am the Fantom,’ and the crowd of Gawkers all laughed. Caleb noticed that Lucius didn’t laugh; instead he grimaced and muttered the words ‘Idiots! What do they know?’ under his breath.

The station exit turnstiles were crowded too. Ahead of them was another Halloween partygoer also dressed in an opera cloak. He gave in his little cardboard ticket to the ticket collector and turned his head as he did so. Caleb saw that he too wore a mask; only this mask was a skull, a death’s head, just like the one he had tucked in his pocket. If Caleb had believed in such things, he would have later thought that it was an omen; but then death masks of every kind were two a penny that night.

.

Chapter 12

Lucius Brown claimed that he carried with him a natural sense of direction, an inner awareness of where he ought to be going, but it was soon clear to Caleb that his father had a very odd idea of where they ought to be going. Once outside the station his father turned to face in what he said he knew was certainly ‘the right direction’. They walked on; Caleb dragged his feet a little way behind his father. They were walking down a long and strangely empty road, which seemed a perverse choice. Caleb was uneasy. He didn’t like the look of the street. It was underlit, with the gas lamps spaced very far apart. It looked as if no one was expected to walk down it in the first place, as if it was an undesignated route.

He felt distinctly nervous away from all the bustling crowds, just the two of them, walking among dark wet shadows. He was not sure whether it was the loneliness of the route, or the darkness, the idea of Halloween, or the growing wisps and tatters of fog all around them, that made him so uneasy.

‘Halloween is an imported festival,’ his father said suddenly, turning back to Caleb. ‘It has been emphasised here falsely in my view. It is an American celebration, grafted on to our past here. For all their boasts of authenticity the Corporation do get things fundamentally wrong sometimes. I once sent a memo about it to Mr Buckland, told him exactly what I thought. Stick to Guy Fawkes, I said. I sometimes doubt that my memos were ever read.’ He turned and walked on. ‘I sense in a real old street like this one an essence or memory of the past. The chaos and pain of past lives which has somehow been pressed, and moulded over the years into these very bricks and stones.’ He stopped and tapped at the wet wall beside them. ‘And I suppose that is one of the main points about the success of Pastworld, of this whol

e place, the saving of the ghosts of the past.’

They walked side by side now. Caleb had allowed himself to catch up. He wondered if his father did not also feel the threat that he sensed all around them in the murk and the shadows. Lucius turned to Caleb and stopped him. He held on to his arm and said almost in a whisper, ‘I know that I have seen complex sophisticated machines which most certainly possessed a soul, and which had more than an inkling of their own existence.’ Caleb frowned; he thought that this was a strange thing for his father to say.

‘Somewhere a long way beneath our feet is a whole other city, very different to this one full of machinery and systems for controlling the fogs and so on,’ Lucius continued.

It was obvious he was distracted and Caleb thought it was no wonder his father was taking them on such a strange route. ‘Are you sure this is the right way? This road seems so dark and empty,’ Caleb said.

‘Bear with me for a moment, Caleb. I have my own reasons for going this way,’ his father said.

The sinister road curved now round the arches and the looming Byzantine brickwork embankments that supported the railway lines. Seen from this angle the foundations of the railway station looked like some newly discovered ruin. They were the freshly revealed archaeological layers of another city and civilisation even more ancient and bleak. The walls were covered over in a seemingly haphazard jumble of thickly lettered posters. One advertised stout, others warned pedestrians to stay on designated routes only. Lucius seemed to be wilfully ignoring that advice.

They passed a signpost. Old Battersea was indicated by a pointing hand, back down the same long, bleak, empty road along which they had just walked. Caleb stopped his father and pointed to the sign.

‘It says here that Old Battersea is back that way?’

‘I know what I am doing, Caleb.’

Pastworld

Pastworld